A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning that makes an argument misleading or unclear. For example, the straw man fallacy means purposefully misinterpreting someone's idea into something easier to attack. The ad hominem fallacy is also well known; it shifts the focus to the person's character instead of the argument itself.

These are only the tip of the iceberg, though. This article will categorize different types of reasoning errors and provide examples of logical fallacies. If you still find it hard to use them correctly in your writing, EssayPro can help. You can ask our professionals to help you structure your work or even order an argumentative essay for sale.

What Is a Logical Fallacy?

A logical fallacy is a pattern of reasoning that looks sound on the surface. Yet, as soon as you pay closer attention, you see the gaps that render the argument invalid. The earlier statements usually don't support the same direction that the final claim moves in. Logical fallacies often appear when someone rushes through the reasoning or faces emotional pressure.

Logical fallacies appear in both spoken and written arguments. They show up when people debate, when they explain opinions, and when they try to persuade. Once you learn to notice the shift away from evidence, the pattern stands out. The skill becomes more natural with practice. Each identified fallacy strengthens your understanding of how reasoning holds together.

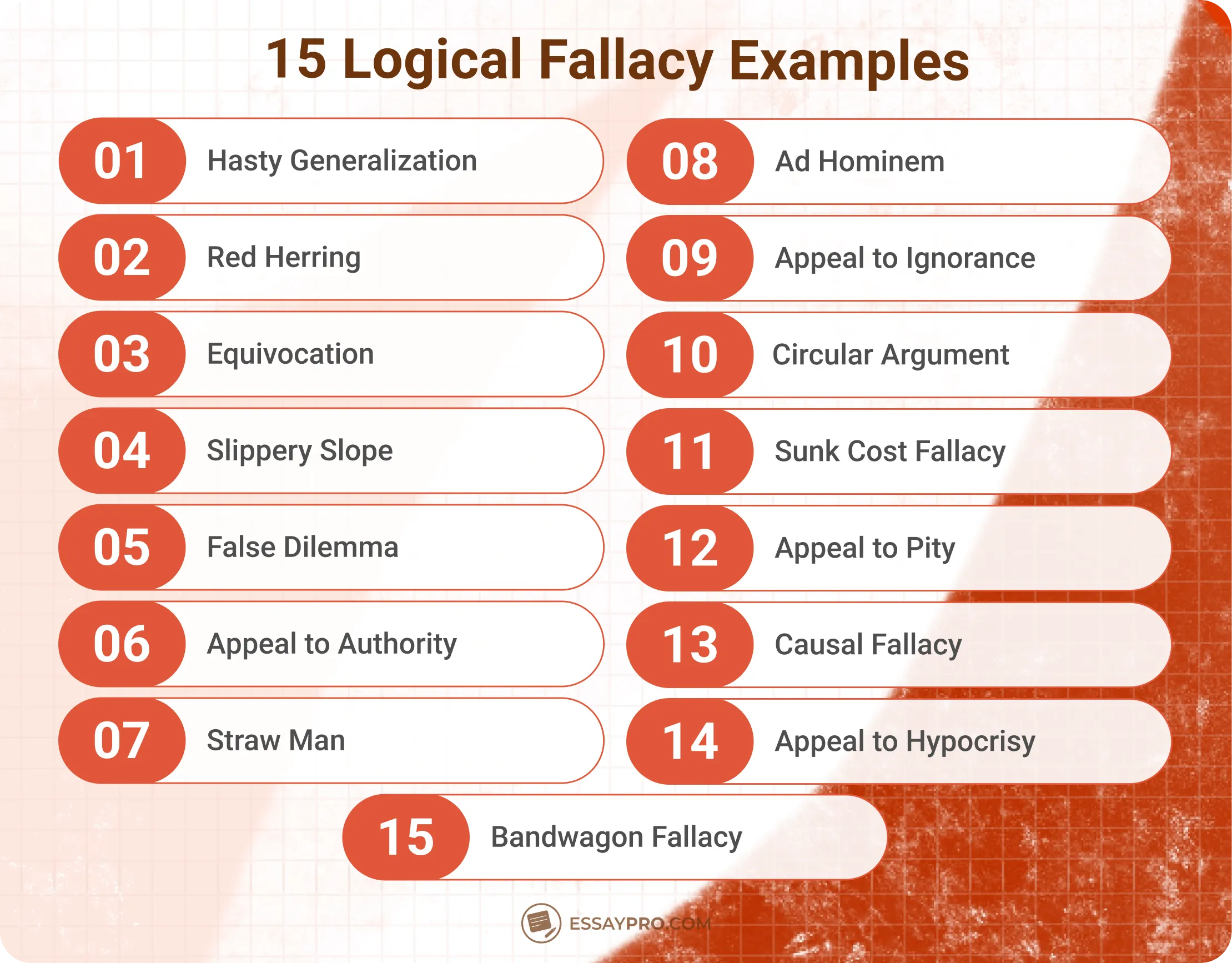

The Most Common Logical Fallacies Examples

You will run into two types of flawed reasoning: formal and informal fallacies. The former happens when the problem is with the argument's validity, whereas with the latter, the point might be valid, but it's not logically related to the conclusion.

Most of the common fallacies are informal:

- Hasty Generalization: reaches a broad conclusion based on limited evidence.

- Red Herring: pulls the discussion toward a different point.

- Equivocation: shifts the meaning of a key term during the argument.

- Slippery Slope: takes a small action and predicts an exaggerated outcome.

- False Dilemma: presents a situation as having only two possible choices, while additional paths exist.

Now, let's get into the list of examples of fallacies in more detail.

Ad Hominem Fallacy Examples

The Ad Hominem argument is one of the informal fallacies that directs attention toward the person instead of the point they made. The response focuses on their traits or identity instead of the soundness of their argument. This is one of the most common logical fallacies examples in media and political debates, where quick reactions are more important than careful reasoning.

Examples of Ad Hominem:

- A student presents research findings. The reply attacks the student’s past grades instead of addressing the data.

- A journalist reports on policy. A commenter accuses the journalist of personal bias and avoids discussing the policy itself.

- A speaker introduces a theory. Someone claims their background disqualifies them, leaving the theory untouched.

You will probably run into logical fallacies in philosophy papers. If you’re trying to make sense of how to write this kind of essay, check out our guide on a philosophy paper format.

Red Herring Fallacy Examples

The red herring fallacy changes the direction of the conversation. The new topic may seem related, but it draws focus away from the original point. The discussion moves sideways instead of forward.

Examples:

- A student questions the cost of supplies. The teacher begins talking about hallway noise.

- Someone raises a concern about water quality. The other person responds by describing vacation weather.

- A debate about grading turns into a conversation about seating arrangements.

Straw Man Fallacy Examples

Straw Man replaces someone’s actual idea with a distorted version that is easier to challenge. The original claim becomes lost.

Examples:

- A student suggests reducing the amount of homework. The reply claims the student wants to eliminate all studying.

- A person mentions fuel efficiency. Another person claims they want driving to be banned.

- Someone recommends healthier cafeteria choices. The critic claims they want to remove every snack option.

Equivocation Fallacy Examples

Equivocation uses a word in more than one sense within the same argument, causing a subtle shift in meaning that distorts the conclusion. The shift changes how the conclusion appears without stating the change.

Examples:

- “A feather is light. Anything light is not heavy. So a feather is never heavy in any way.” The meaning of the word light changes.

- “Laws exist. Everything that exists has purpose. So laws hold moral purpose.” The meaning of exists shifts.

- A person uses the word bank in two different senses and ties the discussion together as if it were one meaning.

Slippery Slope Fallacy Examples

Slippery Slope claims that one small action will trigger a dramatic chain of events without explaining how the chain would form. The outcome sounds urgent, but the steps in between are missing.

Examples:

- “Allowing students to pick essay topics will destroy academic challenge.”

- “Letting taller buildings appear in one area will collapse the city’s structure.”

- “Allowing phones during break time will end focus in the entire school day.”

Hasty Generalization Fallacy Examples

Hasty Generalization draws a broad conclusion from very limited information. The sample is too small. The conclusion reaches farther than the evidence allows.

Examples:

- Meeting a few unfriendly people and deciding that an entire town lacks kindness.

- Experiencing one difficult group assignment and deciding that group work never succeeds.

- Trying one restaurant and forming an opinion about a whole style of cooking.

Appeal to Authority Fallacy Examples

Appeal to Authority relies on a figure’s reputation instead of evidence. The claim depends on who said it rather than why it should be accepted.

Examples:

- A celebrity supports a diet, so someone assumes it works.

- A well-known writer approves of a policy, so the policy is accepted as correct.

- A professor outside the topic area endorses a theory, and the theory is taken as proven.

False Dilemma Fallacy Examples

False Dilemma limits the situation to two choices, even though more options exist. The conversation loses detail. The complexity disappears.

Examples:

- “Support this program, or you oppose progress.”

- “Study this field or reject learning entirely.”

- “Agree with this plan or hope for failure.”

Bandwagon Fallacy Examples

The bandwagon fallacy is another informal fallacy that encourages agreement based on popularity. The argument suggests that just because many people support an idea, it must be correct. The reasoning depends on group behavior instead of evidence or explanation.

Examples:

- A student chooses a side in a debate because most classmates support it, not because the evidence persuaded them.

- A product becomes “the best choice” simply because it trends online.

- A political view is accepted because it dominates social media discussion rather than its reasoning.

If you need help with both the format and the contents of your essay in philosophy, you can ask one of our experts, ‘Write my philosophy paper for me.’

Appeal to Ignorance Fallacy Examples

Appeal to Ignorance claims something must be true solely because no one has proven it false. The absence of evidence becomes the support. The argument treats uncertainty as proof.

Examples:

- “No one has shown this theory to be wrong, so it must be correct.”

- “No clear explanation exists, so the explanation offered now is automatically valid.”

- A student insists a rumor is accurate because no one has publicly denied it.

Circular Argument Fallacy Examples

Circular argument, or circular reasoning, repeats the conclusion as part of the proof. The claim relies on itself, and the argument moves in a loop instead of offering independent support.

Examples of Circular Argument:

- “This rule is fair because it is the rule.”

- “This book is important because important books are included in the curriculum.”

- “This plan works because it is the plan we follow.”

Sunk Cost Fallacy Examples

Sunk Cost holds onto an action because resources have already gone into it. The decision focuses on the time, money, or effort that has been spent, not what makes sense now.

Examples:

- A student continues a failing project because many hours have already gone into it.

- A club keeps a poor strategy because it took weeks to create.

- A person continues watching a show they dislike solely because they have finished several seasons already.

Appeal to Pity Fallacy Examples

The appeal to pity fallacy attempts persuasion through sympathy rather than reasoning. The opponent's argument is based on emotional response rather than the actual logic behind it.

Examples:

- A student requests a higher grade by focusing entirely on personal struggle rather than the quality of the work.

- A speaker argues a policy should pass because it would hurt feelings to oppose it.

- Someone agrees with a position because the other person appears distressed when challenged.

Causal Fallacy Examples

Causal Fallacy assumes one event caused another without showing the connection between them. The link is implied, not demonstrated.

Examples:

- “Test scores improved after the school painted new walls, so the paint caused the improvement.”

- Someone claims a lucky item created their success.

- A minor schedule change is credited for a major outcome with no evidence.

Appeal to Hypocrisy Fallacy Examples

Appeal to Hypocrisy responds to criticism by pointing out the critic's similar flaw. The original point disappears; instead, the focus shifts toward inconsistency rather than addressing the argument.

Examples:

- “You said I should study more, but you didn’t study last semester.”

- A person questions wasteful spending. The reply highlights their unrelated personal purchases.

- A speaker critiques a policy. The response points to a past unrelated mistake instead of discussing the policy.

How to Use Logical Fallacies Right

Arguments move quickly, both in conversation and in writing, so the point of learning logical fallacies is to examine how different parts of the reasoning fit together. You have to break the argument down to find hidden assumptions, rephrase the main claim in your own words, and then carefully test the evidence supporting it. The section below will show you how to work through each step.

Break the Argument into Separate Parts

Take the claim and give it a line of its own. Do the same for the explanation that tries to support it. Then place the conclusion beneath them. Seeing the pieces laid out this way helps you understand how they connect. Many fallacies appear when the conclusion takes a larger step than the support allows. Sometimes the claim sits with no real support whatsoever. Writing the parts separately makes these gaps visible.

Look for the Hidden Step

Arguments often depend on something that goes unspoken. It may be a belief, an assumption, or a familiar idea that no one questions. Ask yourself what the argument needs in order to work. Write the assumption down in plain language. Once the hidden step is named, you can test whether it's backed up by evidence or makes no sense for the situation at all.

Many fallacies rely on weak assumptions. This habit lets you notice those weaknesses early. Let's say, for example, you're part of a discussion about philosophy in the age of AI. Here, you can run into a common hidden assumption that skillful language use equals genuine understanding. The argument can sound persuasive until you pause and examine it closely.

Rephrase the Argument in Clear Language

Speak the argument to yourself in the simplest possible terms. Imagine you are explaining it to someone who has no background in the topic. Use short, direct sentences and keep each idea separate. If the reasoning loses strength when expressed simply, the original version relied on phrasing rather than the strength of logic. Rephrasing gives you a clearer view of the reasoning itself.

Test the Evidence for Specific Detail

Evidence should have something you can point to directly. Look for numbers, events, statements, or sources that can be traced. If the support stays vague or emotional without grounding, the argument stands on shaky ground, while real details give the reasoning a solid foundation. When you evaluate that base, you decide how much you can trust the conclusion.

Wrapping Up: Improve Your Critical Thinking

Logical fallacy detection requires a close look at arguments because they move quickly in writing and conversations, even in social spaces where responses come fast. The most important thing is to notice how the claim, the evidence, and the conclusion build on each other. When these three align, you can confidently identify flawed arguments.

Many students need guidance while they develop their critical thinking skills, particularly when working on academic writing. EssayPro offers essay assistance precisely for moments like that. Our professionals will help you work through real logical fallacy examples and teach you how to develop sound arguments.

FAQs

What Is a Logical Fallacy Example?

A logical fallacy is a flaw in reasoning. The conclusion does not genuinely follow from the statements used to support it. The argument might appear convincing or confident, but the structure falls apart when examined closely. Understanding this helps you evaluate claims with more care.

What Is an Example of a Logical Fallacy?

One of the most common logical fallacies is the Ad Hominem argument. This refers to shifting the focus to your opponent's character instead of the logic in their argument. The speaker changes the subject to avoid addressing the original point.

What Example of Logical Fallacy Do We Use in Daily Conversations?

Hasty Generalization is one of the informal fallacies that appear in everyday life. It happens when someone experiences one situation and treats it as if it represents an entire group or pattern. The mind jumps ahead of the evidence because quick conclusions feel easier than careful analysis.

Which Logical Fallacy Is Often Used in Social Media Debates?

The Appeal to Authority appears often in online discussions. A claim gets accepted because a public figure said it, not because the reasoning holds. The focus shifts to status instead of substance.

What Is an Example of Logical Fallacy False Dilemma?

A False Dilemma presents only two possible outcomes, even though more exist. For instance, someone says, “Either you support this idea or you’re against progress.” The framing removes complexity and pressures agreement instead of allowing thoughtful evaluation.

Annie Lambert

specializes in creating authoritative content on marketing, business, and finance, with a versatile ability to handle any essay type and dissertations. With a Master’s degree in Business Administration and a passion for social issues, her writing not only educates but also inspires action. On EssayPro blog, Annie delivers detailed guides and thought-provoking discussions on pressing economic and social topics. When not writing, she’s a guest speaker at various business seminars.

- Bouchrika, I. (2022, July 18). Logical Fallacies: Examples and Pitfalls in Research and Media. https://research.com/research/logical-fallacies-examples

- University of Miami Ethics Society. (n.d.). Logical fallacies [PDF]. University of Miami. https://ethics.miami.edu/_assets/pdf/um-ethics-society/logical_fallacies.pdf

- Ruggeri, A. (2024, July 10). Logical fallacies: Seven ways to spot a bad argument. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240709-seven-ways-to-spot-a-bad-argument

%20(1).webp)