Webb Discovers Methane, Carbon Dioxide in Atmosphere of K2-18 b

A new analysis of the exoplanet K2-18 b using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has revealed clear signs of carbon-bearing molecules, including methane and carbon dioxide, in its atmosphere. K2-18 b is a so-called sub-Neptune, with a mass about 8.6 times that of Earth. Webb’s measurements support earlier work suggesting that this world may belong to a class of planets known as Hycean exoplanets, which are thought to have hydrogen-rich atmospheres and potentially deep oceans covering their surfaces.

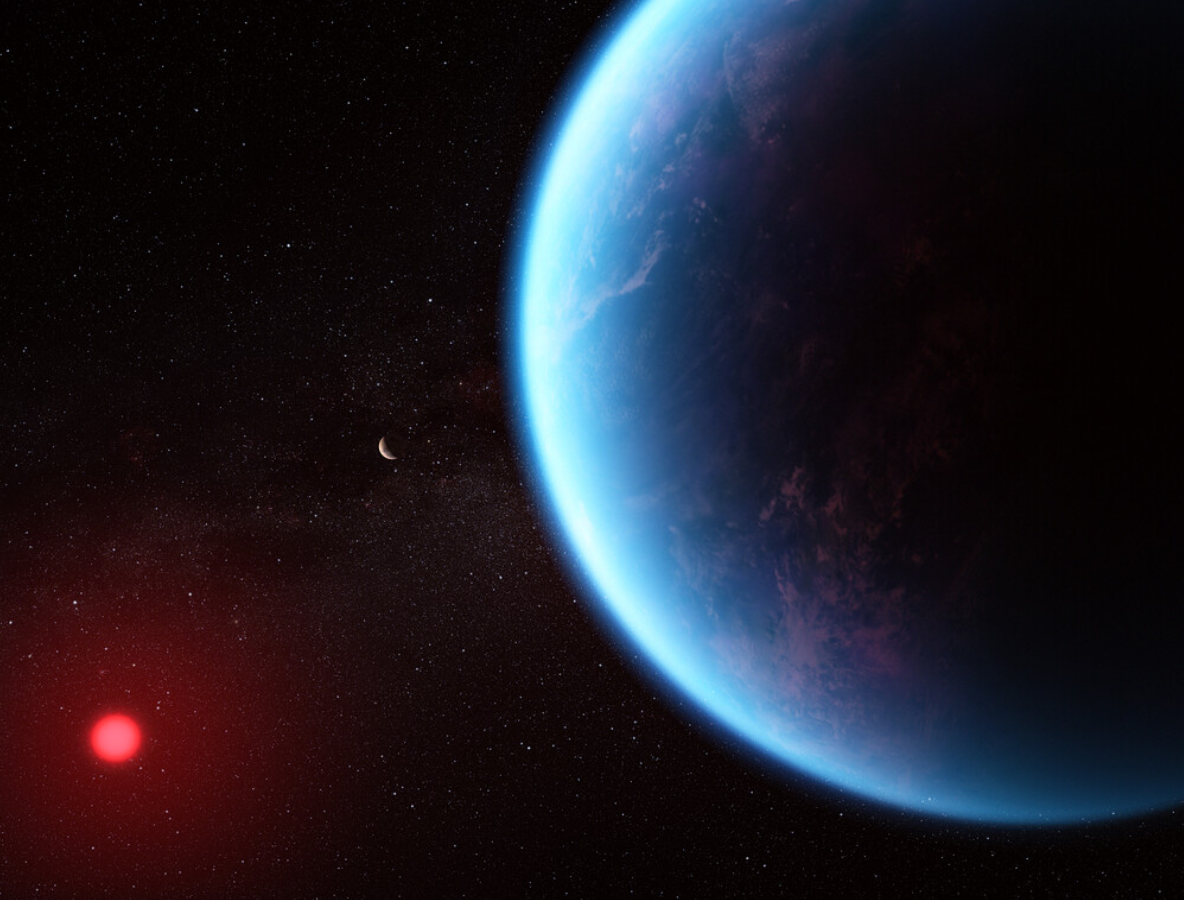

In artist’s impressions based on current scientific data, K2-18 b appears as a large, distant world orbiting a cool dwarf star called K2-18. The planet resides in the star’s habitable zone, the region where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist, and is located roughly 120 light-years from Earth. Webb’s recent observations show strong signatures of methane and carbon dioxide, along with a relative lack of ammonia. This combination is consistent with the idea that a global water ocean could lie beneath a hydrogen-dominated atmosphere on K2-18 b.

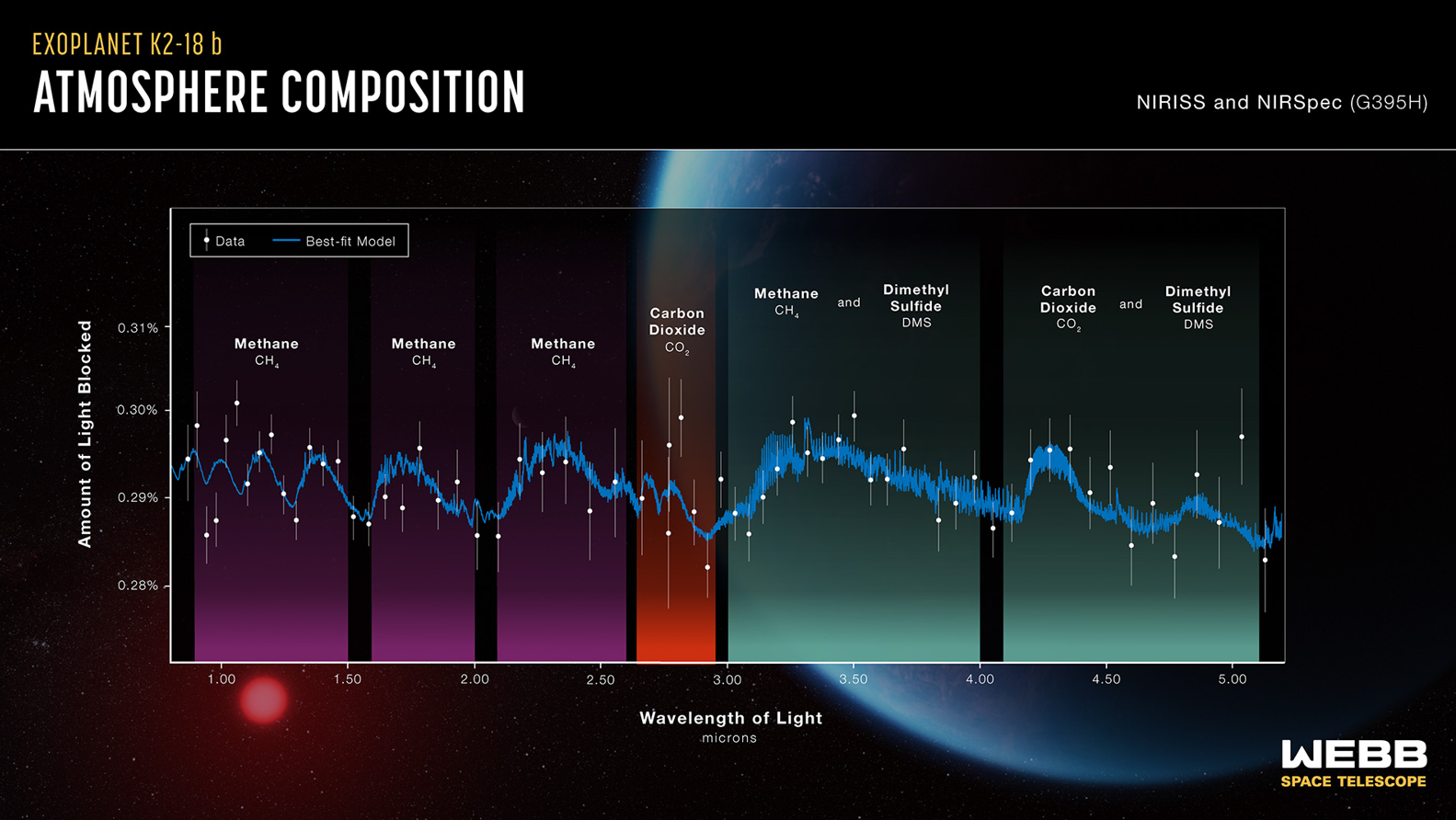

Spectra of the planet, obtained with Webb’s NIRISS (Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph) and NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph), reveal detailed fingerprints of gases in the atmosphere. These data show prominent features from methane and carbon dioxide, and they also hint at the possible presence of dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a molecule that on Earth is primarily produced by marine life. The strong detection of methane and carbon dioxide, together with low levels of ammonia, again points toward a hydrogen-rich atmosphere overlaying what could be an ocean environment on this 8.6-Earth-mass exoplanet.

The potential detection of DMS is still tentative. The signal is not yet strong enough to be considered definitive, and more data are required. As lead researcher Nikku Madhusudhan explains, upcoming Webb observations should help determine whether dimethyl sulfide is truly present in K2-18 b’s atmosphere at significant levels or whether the current hint is simply a statistical fluctuation.

Even though K2-18 b orbits within its star’s habitable zone and now appears to host carbon-bearing molecules, this does not automatically mean the planet is suitable for life. Its relatively large radius, about 2.6 times that of Earth, suggests a structure more similar to Neptune than to a rocky planet. Models indicate that K2-18 b likely has a deep mantle of high-pressure ice, a relatively thin hydrogen-rich atmosphere, and possibly an underlying ocean. Hycean worlds like this are predicted to host global water oceans, but those oceans may be extremely hot or in conditions that are not compatible with life as we know it.

“Planets of this type don’t exist in our own solar system, yet they appear to be the most common planets detected in our galaxy so far,” noted team member Subhajit Sarkar of Cardiff University. “With Webb we have now obtained the most detailed spectrum ever collected for a habitable-zone sub-Neptune, which allowed us to identify the molecules present in its atmosphere with much greater confidence.”

Studying the atmospheres of exoplanets like K2-18 b — identifying which gases are present and under what physical conditions — is one of the fastest-growing areas of modern astronomy. However, these measurements are extremely challenging because the planets are much dimmer and smaller than their host stars. The bright glare of the parent star tends to overwhelm the light coming from the planet itself, making direct observations difficult.

To overcome this problem, the team used a technique known as transmission spectroscopy. K2-18 b is a transiting exoplanet, meaning that it passes in front of its star from our point of view. Each time the planet crosses the stellar disk, a tiny fraction of the starlight filters through the planet’s atmosphere before reaching telescopes like Webb. Different gases absorb light at specific wavelengths, leaving subtle imprints in the spectrum. By carefully analyzing how the starlight changes during these transits, astronomers can infer the composition of the planet’s atmosphere.

“This result was only achievable because of Webb’s wide wavelength coverage and exceptional sensitivity,” Madhusudhan said. “With just two transit observations, Webb delivered spectral precision comparable to what required about eight Hubble transits collected over several years in a narrower wavelength range.” This jump in capability allows scientists to characterize exoplanet atmospheres much more efficiently and in far greater detail than was possible before.

“These findings come from only two observations of K2-18 b, and many more are already planned,” added team member Savvas Constantinou of the University of Cambridge. “What we’re seeing now is just an early example of what Webb can do when it comes to studying planets in the habitable zones of their stars.”

The team’s study has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The researchers now plan follow-up observations using Webb’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) spectrograph. These measurements will help confirm the current detections, test the possible presence of dimethyl sulfide, and refine our understanding of temperature, clouds, and other environmental conditions on K2-18 b.

“Our long-term goal is to identify clear signs of life on a truly habitable exoplanet,” Madhusudhan concluded. “Reaching that point will fundamentally change our understanding of our place in the universe, and our work on Hycean worlds like K2-18 b is an important step toward that objective.”

The James Webb Space Telescope is currently the world’s leading space-based observatory for astrophysics. It is designed to address key questions about the formation of stars and planets, to investigate the atmospheres of distant worlds, and to probe the earliest epochs of cosmic history. Webb is an international collaboration led by NASA in partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).