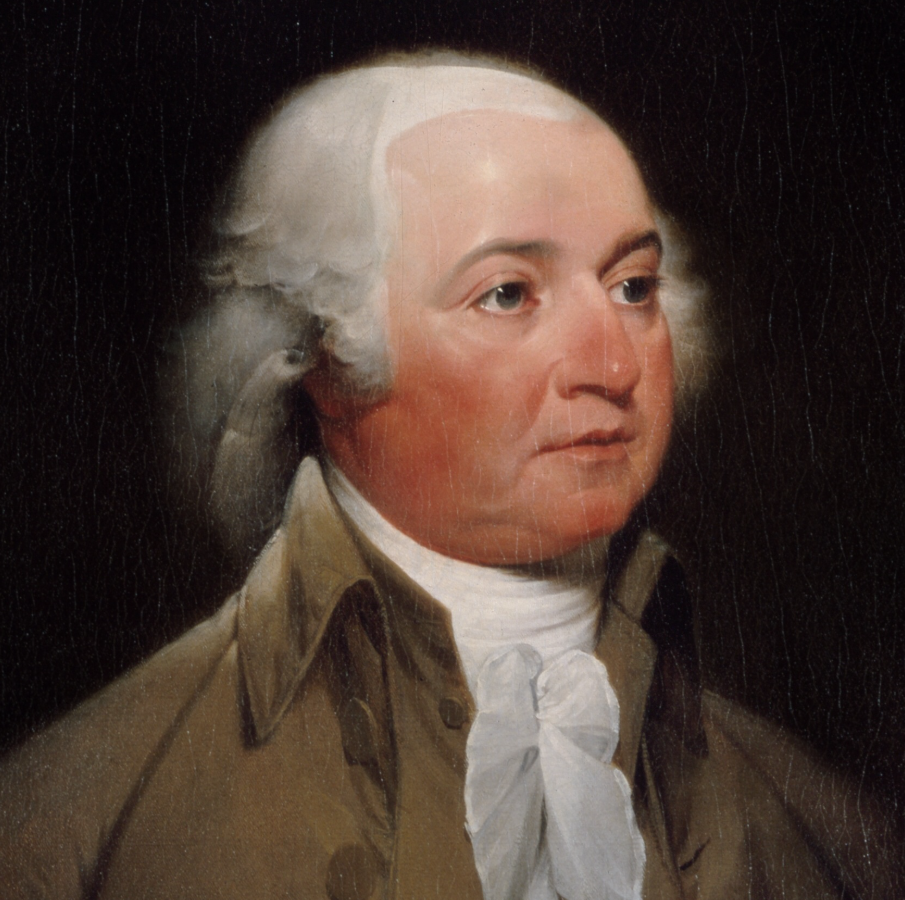

John Adams, widely regarded as an influential political theorist, went on to become the second President of the United States (1797–1801), following his tenure as the nation’s first Vice President in the administration of George Washington.

Learned and deeply reflective, John Adams is often remembered more for his contributions as a political thinker than for his skills as a practical politician. He once observed that “People and nations are forged in the fires of adversity,” a sentiment that clearly reflects both his own life story and the broader American struggle for independence.

Adams was born in 1735 in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. After graduating from Harvard, he built a successful career as a lawyer and quickly aligned himself with the growing patriot movement. As a delegate to both the First and Second Continental Congresses, he emerged as one of the leading voices pushing the colonies toward full independence from Britain.

During the Revolutionary War, Adams played a crucial diplomatic role in Europe. He served in France and the Netherlands, working to secure vital support for the American cause and later helping to negotiate the peace treaty that formally ended the conflict. From 1785 to 1788, he represented the new nation as minister to the Court of St. James’s in London, and upon his return to the United States, he was elected the first Vice President under President George Washington.

For a man of strong energy, keen intellect, and considerable pride, the vice presidency proved to be a source of frustration. Adams famously lamented to his wife Abigail that “My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.” The role offered little real power, and he often felt sidelined in the major decisions of the new government.

When Adams assumed the presidency in 1797, the United States faced serious international and domestic pressures. Ongoing conflict between France and Great Britain was disrupting American shipping and intensifying political divisions at home. Much of his administration’s attention centered on France, where the ruling Directory refused to formally receive the American minister and suspended commercial relations with the United States.

In response, Adams sent three envoys to France to negotiate. However, in 1798 news arrived that Foreign Minister Talleyrand and the Directory had demanded a large bribe before any talks could begin. Adams relayed this affront to Congress, and the Senate published the diplomatic correspondence, identifying the French intermediaries only as “X, Y, and Z.” The disclosure triggered what Thomas Jefferson described as the “X, Y, Z fever,” a wave of anti-French sentiment that Adams himself helped amplify. Crowds cheered the President wherever he went, and the Federalist Party reached the peak of its popularity.

Congress moved quickly to strengthen national defense. Lawmakers approved funds to complete three new frigates, ordered the construction of additional ships, and authorized the creation of a provisional army. They also enacted the Alien and Sedition Acts, laws designed both to intimidate foreign nationals suspected of disloyalty and to curb the influence of opposition Republican newspapers.

Although Adams never asked Congress for a formal declaration of war, armed conflict at sea soon began. At first, American vessels were vulnerable to French privateers, but by 1800 the combination of armed merchant ships and U.S. naval vessels had made the Atlantic sea-lanes significantly safer. American forces scored several notable naval victories, yet public enthusiasm for war gradually diminished.

Eventually, Adams received word that France, too, wished to avoid a full-scale war and was now prepared to negotiate seriously. He chose to send another peace commission, and after lengthy discussions, the two nations ended what came to be known as the “quasi-war.” This decision to seek peace rather than escalate the conflict stirred intense anger among the faction of Federalists aligned with Alexander Hamilton, who accused Adams of weakness and betrayal.

The presidential election of 1800 unfolded against this backdrop of division. The Republicans, united behind Thomas Jefferson, ran an organized and effective campaign, while the Federalists were split and demoralized. Even so, Adams finished only slightly behind Jefferson in the Electoral College, though Jefferson ultimately became President.

Just before that election, on November 1, 1800, Adams traveled to the new federal capital to move into the unfinished White House. On his second night in the cold, damp residence, he wrote to Abigail, “Before I end my letter, I pray Heaven to bestow the best of Blessings on this House and all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise Men ever rule under this roof.” That simple, solemn wish has echoed through American history.

After leaving office, Adams retired to his farm in Quincy, Massachusetts. There he engaged in a remarkable late-life correspondence with Thomas Jefferson, reflecting on the Revolution, government, and human nature. On July 4, 1826 — exactly fifty years after the Declaration of Independence — Adams spoke his final words: “Thomas Jefferson survives.” Unbeknownst to him, Jefferson had died at Monticello only a few hours earlier. Their nearly simultaneous deaths on the fiftieth anniversary of American independence sealed both men’s place in the symbolic and intellectual foundations of the United States.